Mephistopheles

Mephistopheles[a] (/ˌmɛfɪˈstɒfɪliːz/ MEF-ist-OF-il-eez, German: [mefɪˈstoːfəlɛs] ⓘ), also known as Mephostophilis[1] or Mephisto,[2] is a demon featured in German folklore, originating as the chief devil in the Faust legend.[3] He has since become a stock character appearing in other works of arts and popular culture. Mephistopheles never became an integral part of traditional magic.[4] He is also referred to as the Shadow of Lucifer and Prince of Trickery.

During the medieval and Renaissance times, Mephistopheles is equated with the devil due to his high position in the hellish hierarchy. He is one of the seven great princes of Hell, along with being one of the first four angels who rebelled against God and fell. [5]

Origins

[edit]Around the fifteenth to seventeenth centuries in Europe, the age of witchcraft waned, and the Devil became more of a fixture in literature until the later eighteenth century. Once the idea of Satan's "metaphysical existence" seemed less pressing, he became a symbol in literature representing evil characters, evil meanings, corruption, etc. [6] Sometimes, authors had a more sympathetic depiction of Satan, which would later be called the Romantic Devil. Those who believed in pantheistic mysticism[7]— the belief that an individual experiences a mystical union with the divine, believing that God and the universe are one—often held that the angels fell from Heaven because they loved beauty and wanted to have Heaven for themselves. [8] This idea led to the work Faust by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), in which Goethe created his version of the Devil, Mephistopheles. Goethe's Mephistopheles has been highly influential. [9]

Devil vs. Mephistopheles

[edit]The Enlightenment and Romantic eras in Europe increased the variety of views of the Devil. [10] The Devil, also known as Satan or Lucifer, is understood to be the chief adversary of God. He is the leader of the fallen angels and the chief source of evil and temptation. The Devil is the ruler of Hell and is the prince of evil spirits. In the Christian tradition, the Devil is a creation who was subject to the divine will and who misused the divine nature. [11]

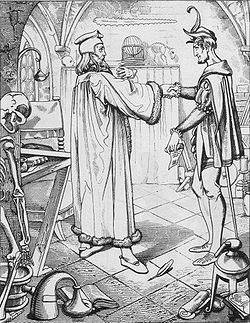

Mephistopheles is seen as Hell's messenger, making him the servant of the Devil. In the Faust legend, he plays the roles of trickster, liar, cheater, and negotiator, making deals for souls, although he can also be intelligent, ironic, and charming. Mephistopheles can shapeshift into any animal, person, knight, etc., through magic and illusion. [12] He is the opponent of beauty and freedom, and he causes the death of the individuals and works to ruin lives. [13]

Etymology and Name Meaning

[edit]The name Mephistopheles is a corrupted Greek compound.[14] The Greek particle of negation (μή, mē) and the Greek word for "love" or "loving" (φίλος, philos) are the first and last terms of the compound, but the middle term is more doubtful.

Three possible meanings have been proposed, and three different etymologies have been offered:

- "not loving light" or "not a friend of light" [1](φῶς, phōs; the old form of the name being Mephostopheles)

- "not loving Faust" or "not a friend of Faust"[1]

- mephitic, pertaining to poisonous vapors arising from pools, caverns, and springs.[14]

Mephistopheles' name was possibly taken from the Hebrew words "mephiz", or destroyer, and "tophel", or slander. The name was invented for the historical alchemist Johann Georg Faust by the anonymous author of the first Faustbuch (published 1587).[2] Mephistopheles was not previously part of the traditional magical or demonological lore. In the play, Doctor Faustus (1604), created by Christopher Marlowe, Mephistopheles was written more as a fallen angel than as familiar demon. In the drama Faust, written in two parts by J.W. von Goethe, Mephistopheles appears as cold-hearted, humorous, and ironic.[15]

In the Faust legend

[edit]

Mephistopheles is associated with the Faust legend, based on the historical Johann Georg Faust. In the legend, Faust, an ambitious scholar, makes a deal with the Devil at the price of his soul, with Mephistopheles acting as the devil's agent. The legend has come to symbolize the consequences of what happens when the quest for empowerment and realization escape the "intellectual and moral restrictions of the Christian medieval order."[16]

The name appears in the late-sixteenth-century Faust chapbooks – stories concerning the life of Johann Georg Faust, written by an anonymous German author. The first of these chapbooks, Historia von D. Johann Fausten (1587) is believed to be the first literary appearance of the Faust and Mephistopheles character.[16] In the 1725 version, which Goethe read, Mephostophiles is a devil in the form of a greyfriar summoned by Faust in a wood outside Wittenberg.

From the chapbooks, the name Mephistophilis entered Faustian literature. Many authors have used it, from Goethe to Christopher Marlowe. In the 1616 edition of Marlowe's The Tragical History of Doctor Faustus, Mephostophiles became Mephistophilis.

In later adaptations of the Faust material, Mephistopheles frequently figures as a title character: in Meyer Lutz's Mephistopheles, or Faust and Marguerite (1855), Arrigo Boito's Mefistofele (1868), Klaus Mann's Mephisto, and Franz Liszt's Mephisto Waltzes. There are also many parallels with the character of Mephistopheles and the character Lord Henry Wotton in The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde.[17]

Mephistopheles in Performance

[edit]Goethe's Faust

[edit]

In Goethe's Faust, the role of Mephistopheles is quite complex, and Josef Kainz describes the role as one of the most significant challenges for an actor in world theater. The character constantly changes in tone throughout the play, giving the character a feeling of minor to no consistency in performance on stage. When Mephisto first meets Faust, he describes how his spirit being “Nothing” conflicts with the world’s spirit of “Something” (Part I Scene III, 1362-1366). The devil is in constant conflict with the world he is placed into, which explains the fluctuation of roles Mephisto portrays on the stage or screen. For an actor to play Goethe's Mephisto, they are called upon to embody this “Nothing” and disconnect themselves from the “Something” that makes them earthly. To achieve this characterization, actors are encouraged to be dramatic and rough in tone and gestures, contradicting traditional elements of classical theater. [18]

Marlowe's Dr. Faustus

[edit]In Marlowe's Doctor Faustus, the roles of Dr. Faustus and Mephistopheles between the two actors, Sandy Grierson and Oliver Ryan, in 2016. While playing both roles, the Scottish actor, Sandy Grierson, expressed that Mephistopheles is more humane than what is portrayed in other plays and novels. [19] The character correlates to the idea of humanity when Mephistopheles pleads with Faustus to reconsider his deal. "O Faustus, leave these frivolous demands" (Act II, Scene 1). Mephistopheles portrays a sense of feeling to prevent Dr. Faustus from making the incorrect decision. Concluding that Mephistopheles is portrayed as less condescending and cold-hearted. Arthur Darvill, who plays as Rory Williams, a companion of the Eleventh Doctor in the television series Doctor Who, even played as Mephistopheles in the 2011 Shakespeare's Globe Theatre's production of Doctor Faustus, expressed how thrilling his experince was on Shakespeare's Globe Youtube Channel. [20]

Interpretations

[edit]

Devil, Damnation, and Hell

[edit]Although Mephistopheles appears to Faustus as a demon – a worker for Lucifer – critics claim that he does not search for men to corrupt, but comes to serve and ultimately collect the souls of those who are already damned. Willard Farnham explains, "Nor does Mephistophiles first appear to Faustus as a devil who walks up and down on earth to tempt and corrupt any man encountered. He appears because he senses in Faustus' magical summons that Faustus is already corrupt, that indeed he is already 'in danger to be damned'."[21]

Mephistopheles is already trapped in his own Hell by serving the Devil. He warns Faustus of the choice he is making by "selling his soul" to the devil: "Mephistophilis, an agent of Lucifer, appears and at first advises Faust not to forego the promise of heaven to pursue his goals".[22] Farnham adds to his theory, "...[Faustus] enters an ever-present private hell like that of Mephistophiles".[23]

Though Mephistopheles can be interpreted as vile through his actions, he profoundly warns Faustus of God’s wrath if he does not repent. Osman Durrani describes the character as “simultaneously, an example of gross depravity and a morally aware theologian.” [1]

Dorothy L. Sayers' play, The Devil to Pay, published in 1939, portrays Mephistopheles as a familiar of the devil as well. Sayers created Mephistopheles to seem mischievous and daunting, while doing the devil's bidding. In this play, it appears as if Mephistopheles' actions were done willingly. Mephistopheles did not necessarily warn Dr. Faustus; rather, he persuaded him to believe that he was to be his servant instead. Once Dr. Faustus was gone, Mephistopheles called into the Hell-Mouth, "Lucifer, Lucifer! The bird is caught..."[Mephistopheles].[24]

This interpretation of Mephistopheles falls in line with the Protestant revisioning of magic, specifically conjuring. In the late 1580's, popular Protestant writers argued that conjurations were "theatrical spectacles", in which Satan allowed demons to appear as if they had been summoned and controlled by humans. This performance further damns the soul of the magician and allows for the demon to collect his soul for Lucifer. These revisions were widely circulated before Marlowe's Dr. Faustus premiered and were integrated into his work.[25]

Nature vs. Evil

[edit]The nature between God and evil is complex amongst the theological issues. In Abrahamic religions, God is inherently deemed as good and not capable of being evil, though those religions also have to acknowledge the existence of evil in the world. Through the ideals of the Society of Jesuits, the Roman Catholic religious order expressed that nature is undistorted by original sin.[26] Mephistopheles also appears as a nature spirit, a Naturgeist.[27] , though he is still deemed as evil or rather destructive amongst many scholars. However, Jane K. Brown suggests that Mephistopheles is Faust's "mediator to the world," that he is neither evil or destructive.[28] Brown suggests that nature is where God and the devil meet and this is where humans live. Mephistopheles, then, represents the one of the two souls that humans naturally possess, Faust's struggle between the "divine principle (mind or spirit) and the world (physical nature)."[29] Mephistopheles is a nature spirit representing the unsegmented world through the human experience. [30]

Sexuality

[edit]One interpretation of the character is that Mephistopheles presents himself as a sexual voyeur. This voyeurism can represent Faust’s sexual confusion and temptation. An example would be Faust’s interactions with Helen of Troy, in which, given temptation, Mephistopheles loosens his grip on Faust as he falls further from God and Heaven. [18]

Mephistopheles can also be perceived as a homoerotic character. When observing male angels during the burial scene in Goethe's Faust, he can be seen as becoming physically aroused. Later on, he becomes consumed by his feelings as he is engulfed in flames. This is believed to be the Lord's plan since the beginning in order to save Faust from damnation. By tempting Mephistopheles's homoerotic nature he is unable to focus on corrupting Faust, subsequently saving him. [1]

See also

[edit]- Beelzebub

- Devil in Christianity

- Prince of Darkness

- Satan

- Mephiskapheles, Ska band whose name is a play on Mephistopheles

- Mr. Mistoffelees, a character from the musical Cats

- Servant, television series

- Mephisto (Marvel Comics) a character from Marvel Comics based on the Demon.

- William Shakespeare mentions "Mephistophilus" in The Merry Wives of Windsor (Act I, Scene I, line 128), and by the 17th century the name became independent of the Faust legend.[31]

Notes

[edit]- ^ Variants of the name include: Mephistophilus, Mephostopheles, Mephistophilis, Mephastophilis, Mephastophiles and others

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Bishop, Paul, ed. (2006). A companion to Goethe's Faust: parts I and II. Studies in German literature, linguistics, and culture (Repr. in paperback ed.). Rochester, NY: Camden House. ISBN 978-1-57113-162-1.

- ^ a b "Mephistopheles". Encyclopedia Britannica. 20 July 1998.

- ^ "Definition of MEPHISTOPHELES". www.merriam-webster.com. 2025-02-17. Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ "Mephistopheles | Faust, Demon, Devil | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 2025-03-03.

- ^ Mason, Asenath (2006). The Book of Mephisto. Edition Roter Drache. ISBN 978-3-939459-00-2.

- ^ Easlea, Brian (1989-02-01). "<scp>jeffrey burton russell</scp>. Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1986. Pp. 333. $24.95". The American Historical Review. 94 (1): 105–106. doi:10.1086/ahr/94.1.105. ISSN 1937-5239.

- ^ Starr, Reginald H. (1901). "Christian Mysticism". The Sewanee Review. 9 (1): 30–40. ISSN 0037-3052.

- ^ "Joseph, Mary, and baby Jesus in cage". doi.org. doi:10.3998/mpub.9956530.cmp.24. Retrieved 2025-04-29.

- ^ Easlea, Brian (1989-02-01). "<scp>jeffrey burton russell</scp>. Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1986. Pp. 333. $24.95". The American Historical Review. 94 (1): 105–106. doi:10.1086/ahr/94.1.105. ISSN 1937-5239.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton (2016-03-10). The Prince of Darkness. Cornell University Press. doi:10.7591/9781501703331. ISBN 978-1-5017-0333-1.

- ^ Easlea, Brian (1989-02-01). "jeffrey burton russell . Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World . Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1986. Pp. 333. $24.95". The American Historical Review. 94 (1): 105–106. doi:10.1086/ahr/94.1.105. ISSN 1937-5239.

- ^ Russell, Jeffrey Burton (2016). The Prince of Darkness: Radical Evil and the Power of Good in History. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-1-5017-0333-1.

- ^ Easlea, Brian (1989-02-01). "jeffrey burton russell . Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World . Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1986. Pp. 333. $24.95". The American Historical Review. 94 (1): 105–106. doi:10.1086/ahr/94.1.105. ISSN 1937-5239.

- ^ a b Snider, Denton Jaques (1886). Goethe's Faust: A commentary. Sigma. pp. 132–133.

- ^ Lackland, Caroline Eliot (1882). "Mephistopheles". The Journal of Speculative Philosophy. 16 (3): 320–329. ISSN 0891-625X.

- ^ a b Zapf, Hubert (2012). "The Rewriting of the Faust Myth in Nathaniel Hawthorne's "Young Goodman Brown"". Nathaniel Hawthorne Review. 38 (1): 19–40. doi:10.5325/nathhawtrevi.38.1.0019. ISSN 0890-4197.

- ^ {{Cite He is also interpreted as a mysterious figure in the movie Ghostrider. web|url=https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/english/currentstudents/undergraduate/modules/fulllist/special/interdisciplinaryandcreativecollaboration/faustbooks/doriangray/%7Ctitle = The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde (1891)}}

- ^ a b Brown, Jane K.; Lee, Meredith; Saine, Thomas P., eds. (1994). Interpreting Goethe's "Faust" today. Columbia, SC: Camden House. ISBN 978-1-879751-49-1.

- ^ "Sandy Grierson | Blog | Royal Shakespeare Company". www.rsc.org.uk. Retrieved 2025-04-29.

- ^ Shakespeare's Globe (2011-06-14). Shakespeare's Globe Theatre: Doctor Faustus interview with Arthur Darvill. Retrieved 2025-04-29 – via YouTube.

- ^ Farnham, Willard (1969). Twentieth Century Interpretations of Doctor Faustus. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 978-0132163095.

- ^ Krstovic, Jelena; Lazzardi, Marie, eds. (1999). "Plot and Major Themes". Literature Criticism from 1400 to 1800. 47. Detroit, Michigan: The Gale Group: 202.

- ^ Krstovic & Lazzardi 1999, p. 8

- ^ "Villainy and the Life of the Mind in A.S. Byatt and Dorothy L. Sayers". The Devil Himself: 147–158. 2001. doi:10.5040/9798400639760.0015. ISBN 979-8-4006-3976-0.

- ^ Guenther, Genevieve (August 2011). "Why Devils Came When Faustus Called Them". Modern Philology. 109 (1): 46–70. doi:10.1086/662147. ISSN 0026-8232.

- ^ Russell, Jeffery (1986). Mephistopheles (4th ed.). Cornell University Press. ISBN 9780801418082.

- ^ Brown, Jane K. (1985). "Mephistopheles the Nature Spirit". Studies in Romanticism. 24 (4): 475–490. doi:10.2307/25600562. JSTOR 25600562.

- ^ Brown, Jane K. (1985). "Mephistopheles the Nature Spirit". Studies in Romanticism. 24 (4): 475–490. doi:10.2307/25600562. ISSN 0039-3762.

- ^ Brown, Jane K. (1985). "Mephistopheles the Nature Spirit". Studies in Romanticism. 24 (4): 475–490. doi:10.2307/25600562. ISSN 0039-3762.

- ^ Easlea, Brian (1989-02-01). "jeffrey burton russell . Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. 1986. Pp. 333. $24.95". The American Historical Review. 94 (1): 105–106. doi:10.1086/ahr/94.1.105. ISSN 1937-5239.

- ^ Burton Russell 1992, p. 61 8. "Call Me Little Sunshine" by heavy-metal band Ghost 2022

Bibliography

[edit]- Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1986). Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World (1990 reprint ed.). Ithaca, New York: Cornell. ISBN 978-0-8014-9718-6.

- Goethe, Johann Wolfgang Von (2001). Hamlin, Cyrus (ed.). Faust: A Tragedy; Interpretive Notes, Contexts, Modern Criticism (Norton Critical ed.). New York, New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-97282-5.

- Ruickbie, Leo (2009). Faustus: The Life and Times of a Renaissance Magician. Stroud, UK: History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-5090-9.

- Andersson, Love. ““The Devil to Pay” : Temptation and Desire in Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus.” DIVA, 2021, www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A1527786&dswid=197

- Smith, Warren D. “The Nature of Evil in “Doctor Faustus.”” The Modern Language Review, vol. 60, no. 2, Apr. 1965, p. 171, https://doi.org/10.2307/3720056

External links

[edit] Quotations related to Mephistopheles at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Mephistopheles at Wikiquote The dictionary definition of Mephistophelean at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of Mephistophelean at Wiktionary